Interviewed by Rachel Balko

Interviewed by Rachel Balko

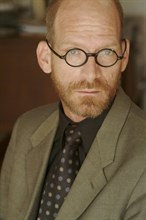

Ron West has been a successful comedy writer for more than 30 years. His television writing credits include “Second City This Week” (2011-2012) and “Whose Line Is It Anyway?” (1999-2006). He was the head writer for the pilot of “The Second City’s 149 1/2 Edition” (1994), and has contributed to other syndicated TV shows. His musical comedy, The People vs. Friar Laurence, the Man Who Killed Romeo and Juliet, was published by Samuel French in 2010. Ron has written, directed, and performed more shows for Second City than he can count, collaborating with performers such as Steve Carell, Stephen Colbert, Scott Adsit, Jane Lynch, and Rose Abdoo. Ron was a contributing writer on the book, The Second City Almanac of Improvisation, and currently teaches comedy writing and improvisation at the Second City Training Center in Hollywood, California. Ron was generous with both his time and his talent in answering these questions about his life as a writer via email.

How did you become a writer?

I looked the part, so one day someone said, “You are going to write this,” so I did. I don’t remember the exact date and time.

Who are some of your early influences, and which writers do you admire today?

I liked Monty Python when I was a kid. I “discovered” them in reruns on PBS in the ’70s. I think the screenplay for The Godfather Parts 1 and 2 are the best screenplays ever. I have read all of Vonnegut, and I think the screenplay for Slaughterhouse-Five is great. I am one of only six people to read all of Nicholas Nickleby, so I guess I must like Dickens. I’ve only recently delved into Shakespeare more. Whose writing do I admire today? Well, I thought “30 Rock” was very well crafted. I liked “House of Cards.” I liked “Friday Night Lights,” but I made the mistake of watching them all back to back, which tended to step on the reality of it all. I became aware that That Much cannot happen to Ordinary People. I read a lot of nonfiction, so the guy who wrote Guns, Germs, and Steel is tops. The only book I have ever read twice is Enemies at the Gate by William Craig, which was made into a terrible movie. So go figure.

How useful is formal education for aspiring writers?

I don’t know. I can only say I wish I’d had more of it.

Do you remember the first piece you had published or produced? What was it, and what was the experience like for you?

I wrote stuff in college and before I joined Second City, but the first time I got paid for writing was for an industrial or corporate show. I think the client was American Hospital Supply. Meagan Fay, Roger Muellar, and Gerry Becker performed some sketches I wrote, one of which was a Wizard of Oz parody. I was incredibly proud. Like the way the parents are proud of their kids’ musicianship in The Music Man.

On your website (www.ronwestnow.com), you describe yourself as a “Writer/Director/Actor.” Why does “writer” come first?

Because the late Bernard Sahlins, one of my mentors at Second City, said, “Directing is writing. Acting is writing.” Also, the three words just sound better in that order.

Your musical comedy, The People vs. Friar Laurence, the Man Who Killed Romeo and Juliet (which you co-wrote with Phil Swann), is the most financially successful production in the history of the Chicago Shakespeare Theater, and other productions of the play have been popular as well. To what do you attribute the appeal of The People vs. Friar Laurence?

Although few people really know Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, everyone thinks they do, so I was sort of able to exploit the audience’s common knowledge. Phil and I had a lot of fun working on it, and I let Shakespeare do most of the heavy lifting. I also referred to my notes that I took on the play from when I was in high school, when I knew how to take notes. Lastly, the book and the songs (which have very appealing Swann/West melodies, I must say) tell the audience, “Get on the train, or get left at the station.”

As a writer for stage and television, how do you approach the writing process? Do you write primarily to please yourself (with the hope, one assumes, that others will enjoy your work)? Or do you consider how each word will be interpreted, first by the actors and eventually, by the audience?

Having pondered your question, I would say I just try to write to make sense for me. I don’t really think about the actors, and I don’t really think about the audience. One time a producer told me, “We have to do x and y, especially with this audience,” and I ignored him.

How does your experience as a performer inform your work as a writer, and vice versa?

- There are some things that are funny coming out of my mouth that are not funny coming out of other people’s mouths.

- I did a show last year where I was just a hired gun as an actor, and I was not as respectful toward the words as I would expect an actor to be toward mine. In my defense, the words I was given were decidedly lacking at times.

- At the end of the day, you have to do the gig for which you were hired. Because everybody is trying to cut costs (televised improv is just a way to cut costs), I often find myself applying more than one discipline. Like, I’m an actor, but we have to change these words.

You’ve worked with Second City, one of the oldest and most famous comedy theatres in the United States, for a number of years, and you’ve collaborated with many writers and performers who’ve gone on to great success. Are there any Second City stories you’d like to share?

One time I was directing a show that featured the soon-to-be stars Stephen Colbert, Ian Gomez, and Jackie Hoffman. The cast had a scene featuring geeky kids who lived on a mountain with a scientist. The cast loved the scene and I hated it. One day, I told them the Seven Things I thought we needed to do to make the scene work. It was probably the most I’ve ever spoken about one scene. After I thought I had delivered a convincing lecture on How to Fix the Scene, Jackie said, “Well, maybe if we made it goofier,” and I feared my efforts were in vain. We put my notes into effect, but we didn’t have an ending. On a Tuesday afternoon, Ian Gomez said, facetiously, “What if we did the whole scene backwards?” and I said, “Yes, that’s it!” That was the ending, and we opened to raves on Thursday.

Second City is famous for producing talented improvisers, but scripted sketch comedy is the backbone of the theatre’s comedy revues. How do you view the relationship between improvised and scripted comedy?

Everyone wants to improvise, where you get credit for shitty work, and no one wants to write, where you get no credit for labor. The thing at Second City is to find some gem when you’re improvising and polish it with writing. It is a myth that the scenes are improvised and are magically put into the show. There are many dumb improvisations that are rightfully ignored. Only once or twice did I witness/participate in an improv that was repeated in the same way as a written scene.

Many people think of writing as a solitary profession, but you have collaborated with musician Phil Swann on several musicals (The People vs. Friar Laurence and deLEARious are two), and sketch comedy is often written collaboratively as well. Do you use a different writing process when working alone versus working collaboratively? Do you prefer one to the other?

Yes. No.

Do you have a favorite piece that you’ve written?

Well, I love The People vs. Friar Laurence, I love deLEARious, and I love all our Shakespeare songs. I helped to craft a devastatingly funny sketch called “Ventriloquist” at Second City which was a paragon of collaboration. I created a couple of games for “Whose Line Is It Anyway?” that people are still having fun with. Oh, I wrote a “Bon Voyage” sketch for my friend, Bill Thomas, at church. That got a lot of laughs.

What projects do you currently have in the works?

I am working on some one-acts with the far more successful playwright Catherine “Kick” Butterfield.

Your plays have received theatrical awards and nominations in Chicago and Los Angeles (2008 Jeff Award [Chicago] for Best New Adaptation for The Comedy of Errors at Shepperton, 1940; Nomination for 2008 Los Angeles Stage Alliance Ovation Awards’ Franklin R. Levy Award for Musical in an Intimate Theatre for deLEARious). How much attention do you pay attention to the critics?

I only pay attention when they’re right.

What does it take to be a successful writer?

I will get back to you when I become one.

Many writers enjoy writing, but dislike the business aspects of the profession (e.g., finding an agent, pitching their work). How do you feel about the commercial aspects of being a writer, and do you have any advice on how to handle them?

The business side is tough for me. One time we had a producer say to us, “This is the most successful show we have ever had.” Then his partner said, “This is too expensive to produce.” I didn’t know what to say, but I thought Phil [Swann] was going to rip off his own head and throw it at them.

Any additional words of wisdom for those pursuing a career as a writer?

Don’t bet the farm on a Big Reveal on the Last Page of Your Script.

Rachel Balko is a writer and librarian. She is co-author of The Canada IFLA Adventure: 85 Years of Canadian Participation in the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, 1927 to 2012, which was published in 2013. She is currently writing a young adult novel as her thesis for the Master of Arts in Children’s Literature degree at the University of British Columbia.